Browse the Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive for Civil War era newsapers

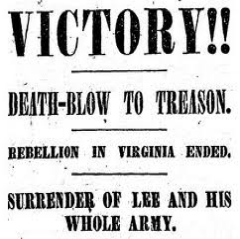

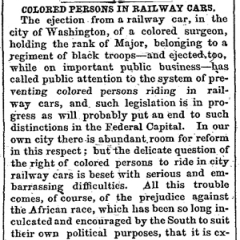

Newspapers were the dominant media of the Civil War era. The period is notable for the rise of the penny press, forerunners of the modern newspaper. These ostensibly independent journals were characterized by their small size (easier to read on bustling city streets), sensational stories of urban life, and cheap price (appealing to the laboring classes). These qualities created mass appeal for penny papers such as Baltimore’s Sun, New York’s Herald and Tribune, and others which achieved circulations in the tens of thousands. Though these were the largest newspapers of the day, they were the exception rather than the norm. By 1860, over 80% of the nation's newspapers were small-circulation partisan journals that promoted the interests of a given political party and in turn were sustained by the subscriptions of party members and government patronage. Editors of partisan newspapers also often served as party administrators, serving on committees that organized conventions, selected candidates for office, and hired individuals to work the polls and turn out the vote on election days. While party newspapers and penny presses dominated the field, newspapers dedicated to other interests, such as moral reform, family entertainment, sporting life and urban vice, and commercial news rounded out this vibrant newspaper market.

The federal government subsidized the dynamic growth of newspapers in this period. The Post Office encouraged the broadcast distribution of papers by shipping them through the mails at sharply discounted rates. Postal laws also extended the franking privilege to editors, allowing them to share newspapers with each other through the mails free of charge. This enabled editors who lacked reportorial staffs to fill out the pages of their papers with content clipped from other journals. In addition to these subsidies, a growing population, westward migration, innovations in printing press technology, and party patronage all contributed to the remarkable growth of the antebellum American press from approximately 200 newspapers in 1801 to roughly 1,200 by 1835. Newspapers reached far beyond individual subscribers, typically being read aloud in public gatherings at hotels, court days, the local post office, taverns, marketplaces, and other public spaces. These organs connected far-flung communities, enabled the development of national political parties, and promoted the country’s continental expansion and economic growth. Civil War era newspapers did not just record American history in this period, but actively shaped that history.

For more information on Civil War era newspapers, see Frank Luther Mott, American Journalism: A History of the Newspaper Through 250 Years, 1690 to 1940 (New York: Macmillan, 1941); Richard John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1995); Thomas C. Leonard, News For All: America’s Coming of Age with the Press (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); and Michael Schudson, The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life (New York: The Free Press, 1998).